An estimated 30 percent of the world is infected with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, including 60 million people in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Mary Carter, second-year student at Ohio State’s College of Veterinary Medicine, spent her summer at Stanford University studying the molecular underpinning of the parasite and its infectious processes in mice.

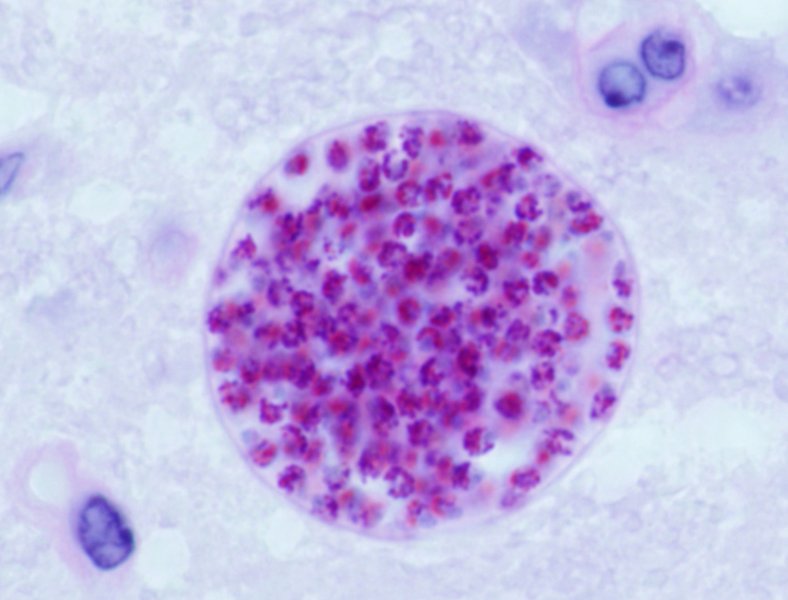

“T. gondii is a very complex and successful parasite,” Carter said. “We’re still trying to figure out how it infects such a broad range of hosts while simultaneously altering the host’s immune response to avoid detection.”

Mary Carter, second-year veterinary student (bottom right), poses with her research team, including Drs. John Boothroyd and Sarah Ewald, at Stanford University in August 2015.

The parasite causes a condition called Toxoplasmosis, which can cause a range of issues in people who don’t have a fully functioning immune system, including fever, pneumonia, chronic inflammation, central nervous system disorders and fatality. Most healthy adults are asymptomatic and completely unaware they are infected.

T. gondii lives and reproduces in cats without affecting them. Most humans and other intermediate hosts (such as mice) are presumed to acquire it through exposure to infected cat feces or poorly cooked food. It can also be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, which is why pregnant women are strongly advised to avoid scooping cat litter. There are two stages of T. gondii infection: acute and chronic. If caught in the acute stage, the disease can be treated, but since it’s hard to detect and requires a specific blood test it often moves to the chronic stage, creating cysts in muscle and brain tissue. Recent studies have linked T. gondii with an increased incidence of mental disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, which is plausible since it affects the brain.

When mice are infected with T. gondii, they show lethargy, severe weight loss and intestinal inflammation during the acute stage, Carter said. After about 14 days they start to recover, but the weight loss and stunted growth (called wasting) remains for the rest of their lives.

Carter and her research team at Stanford (shown on right) want to understand how T. gondii causes weight loss in mice by examining its molecular processes throughout infection. They also measured differences in food intake, body weight, muscle and fat mass. Results are currently pending, and will be useful in understanding the wasting processes that occur in diseases like MS, cancer cachexia or chronic kidney disease.

Carter said she was interested in infectious disease research because her cat died of Feline Infectious Peritonitis when she was young, and there was very little information about why FIP occurred in cats or how it was treated.

“There are still so many diseases, including emerging diseases, that we don’t understand,” she said. “We have a lot of great information on T. gondii, but there is still a lot to learn.”

Toxoplasmosis is considered a “Neglected Parasitic Infection,” one of five parasitic diseases that the CDC has identified for public health action.

Comments are closed