The articles below are from a series of 25 stories I wrote on studies conducted by veterinary students in the The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine’s 2015 Veterinary Scholar Summer Research Program.

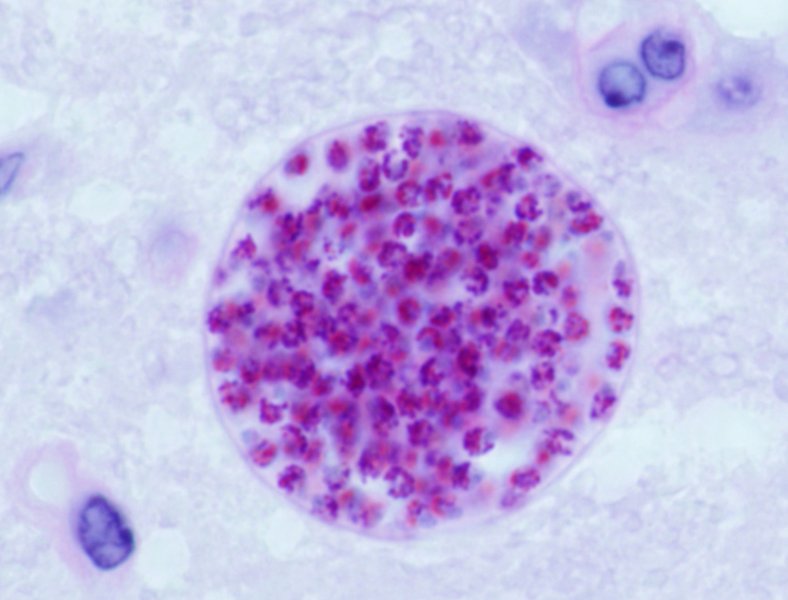

Studying effects of Toxoplasma gondii on mice

An estimated 30 percent of the world is infected with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, including 60 million people in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Mary Carter, second-year student at Ohio State’s College of Veterinary Medicine, spent her summer at Stanford University studying the molecular underpinning of the parasite and its infectious processes in mice.

“T. gondii is a very complex and successful parasite,” Carter said. “We’re still trying to figure out how it infects such a broad range of hosts while simultaneously altering the host’s immune response to avoid detection.”

Mary Carter, second-year veterinary student (bottom right), poses with her research team, including Drs. John Boothroyd and Sarah Ewald, at Stanford University in August 2015.

The parasite causes a condition called Toxoplasmosis, which can cause a range of issues in people who don’t have a fully functioning immune system, including fever, pneumonia, chronic inflammation, central nervous system disorders and fatality. Most healthy adults are asymptomatic and completely unaware they are infected.

T. gondii lives and reproduces in cats without affecting them. Most humans and other intermediate hosts (such as mice) are presumed to acquire it through exposure to infected cat feces or poorly cooked food. It can also be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, which is why pregnant women are strongly advised to avoid scooping cat litter. There are two stages of T. gondii infection: acute and chronic. If caught in the acute stage, the disease can be treated, but since it’s hard to detect and requires a specific blood test it often moves to the chronic stage, creating cysts in muscle and brain tissue. Recent studies have linked T. gondii with an increased incidence of mental disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, which is plausible since it affects the brain.

When mice are infected with T. gondii, they show lethargy, severe weight loss and intestinal inflammation during the acute stage, Carter said. After about 14 days they start to recover, but the weight loss and stunted growth (called wasting) remains for the rest of their lives.

Carter and her research team at Stanford (shown on right) want to understand how T. gondii causes weight loss in mice by examining its molecular processes throughout infection. They also measured differences in food intake, body weight, muscle and fat mass. Results are currently pending, and will be useful in understanding the wasting processes that occur in diseases like MS, cancer cachexia or chronic kidney disease.

Carter said she was interested in infectious disease research because her cat died of Feline Infectious Peritonitis when she was young, and there was very little information about why FIP occurred in cats or how it was treated.

“There are still so many diseases, including emerging diseases, that we don’t understand,” she said. “We have a lot of great information on T. gondii, but there is still a lot to learn.”

Toxoplasmosis is considered a “Neglected Parasitic Infection,” one of five parasitic diseases that the CDC has identified for public health action.

Raw pet food is growing in popularity, but is it safe?

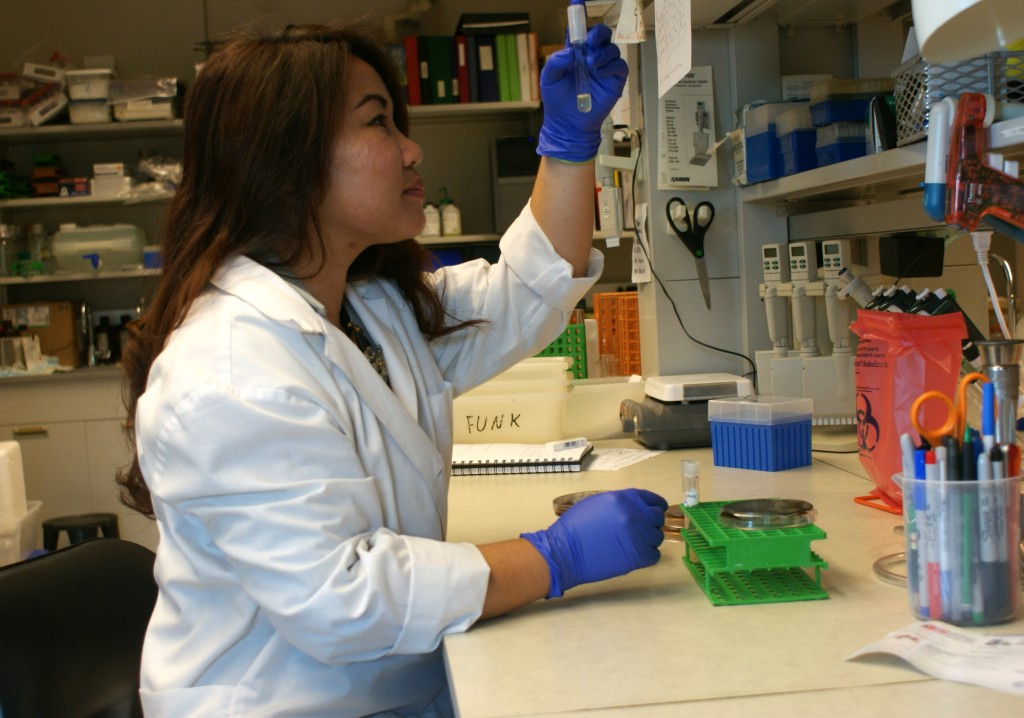

Raw pet food has a growing consumer base, says Paulynne Bellen, third-year veterinary student at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, but the food may not come without health risks.

One concern is that raw pet food can sometimes carry a bacterium called Listeria monocytogenes, among other foodborne bacteria, since it does not go through the cooking and steaming processes that dry pet food does.

If ingested, L. monocytogenes can cause more extreme symptoms than E. coli, such as infection, fever, gastrointestinal problems and sometimes death. The bacterium can survive in low temperatures and in the presence or absence of oxygen, which is how it likely gets into some raw pet food. L. monocytogenes poses a much higher risk for animals (including humans) that are immunocompromised.

Bellen and Dr. Thomas Wittum, research mentor, professor and interim chair of the Department of Veterinary Preventive Medicine at Ohio State, are testing 120 raw pet food samples for the presence of L. monocytogenes, E. coli and Salmonella. They are comparing the levels of foodborne pathogens found in each sample to the four standard processing methods used in raw pet food production: freeze drying, high-pressure pasteurization, raw freezing and dehydration.

Paulynne Bellen, third-year veterinary student at The Ohio State College of Veterinary Medicine, analyzes a sample of raw pet food for foodborne pathogens as part of a study funded by the college’s Veterinary Scholar Summer Research Program

This does not mean that all raw food is unsafe for pets to eat or without its benefits, and some veterinarians regularly recommend it, Bellen said.

“As a scientist, you can’t be swayed either way without the facts,” she said. “We just want to determine if one processing method is better at keeping bacteria out than the others, which would allow us to guide pet owners toward the safest kinds of raw food.”

The FDA has issued recalls on several major raw pet food brands and companies in recent years, including three in 2015, brand names Primal, OC Raw Dog and Vital Essentials .

Bellen said that the study has improved her skills in the lab and in responding objectively to a controversial issue. The team expects to see several food samples test positive for foodborne bacteria, Wittum said.

Testing therapeutics on feline lung cancer

Dylan Burroughs, second-year student at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, is working on some of the world’s first research on Feline bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC), a form of lung cancer.

The best method for researchers to study BAC without running tests on a cat is to use a live model of the cancer, called a cell line. Worldwide, there is only one feline BAC cell line available, so he and his mentor Dr. Gwendolen Lorch, assistant professor at Ohio State in Veterinary Clinical Sciences, had to wait a while to acquire it for their research.

The team used the cell line to test different concentrations of drugs and how they work in controlling the cancer. They also measured gene and protein expression levels to know what cell regions should be targeted during treatment.

It is typical in human lung cancer for the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a protein that takes part in cell communication, to be overexpressed. The overexpression of EGFR and related genes leads to an overabundance of cells, which could play a large role in causing the cancer, Burroughs said. In an attempt to stem the excess cell growth, Lorch and Burroughs are testing the effect of EGFR inhibitors on the feline BAC cell line in addition to standard cancer-treatment drugs.

Dylan Burroughs, second-year veterinary student at Ohio State, works in the lab with a feline cell line. July 21, 2015; Columbus, Ohio.

In cats, this type of cancer tends to metastasize – or spread – to the paws. This complicates the effectiveness of treatment options because the tumors are growing in complex patterns that are hard to recognize and target.

The results of the study could potentially help human lung cancer research, but the team is mainly working on establishing normal values for feline BAC that will guide future scientists. They are also focused on understanding the method in which the tumors are able to spread from the lungs to the paws.

Burroughs’ study is being funded by the National Institute of Health, and he presented his findings at the 2015 Merial-NIH Veterinary Scholars Symposium at UC Davis.

Hearts of infant mice have self-healing abilities, researchers look closer

Did you know that some amphibians and fish have hearts that regenerate muscular tissue cells following injury? This healing mechanism, called cardiac regeneration, is sustained throughout the creatures’ lives.

But for humans and other mammals, the heart’s reparative ability is confined to a small window of time during infancy. For mice, studies have shown that this window of time is about seven days. The heart of an infant mouse will self-repair in response to damage during this period, after which the capacity for cardiac regeneration is lost.

Sylvie Cohen (Far Left) with the other vet students that participated in the NIH internship program and the two directors of the program (Dr. Mark Simpson, DVM, PhD and Dr. Chuck Halsey, DVM, PhD).

Sylvie Cohen, second-year student at Ohio State’s College of Veterinary Medicine closely examined cardiac regeneration processes in one-day-old mice this summer at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Cohen’s focus was on studying the molecular and cellular channels underlying heart-regeneration in mice.

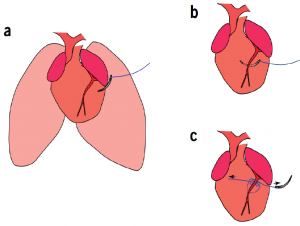

Cohen and her team worked in the lab of Dr. Toren Finkel, senior investigator at the NIH’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology. First, the team wanted to test whether the infant mice’s hearts would actually repair themselves following injury. To do this, a microsurgery was performed on the experimental group that involved cutting off blood supply to the left anterior descending coronary artery, inducing a heart attack (modeled in figure below).

To establish how the neonatal mouse heart responds to ischemic injury, Cohen and her team permanently ligated the left anterior descending coronary artery of 1-day-old mice.

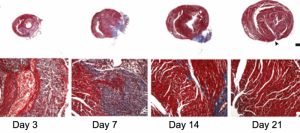

After 21 days, the mice that had heart attacks had fully recovered as their hearts had gradually generated new muscular tissue. Cohen and her team were able to see the cardiac regeneration process in action through histologic analyses of the mice’s heart tissue. As seen in the figure to the left the heart increasingly repaired itself over time, getting back to normal around day 21.

In addition to testing the mammalian heart’s capacity to regenerate for a brief period after birth, Cohen and her team also looked at what they consider a key-regulator in the cardiac regeneration process: a gene called BMI1. BMI1 has been shown to play an important role in cardiac muscle development, so researchers have hypothesized that it’s vital during cardiac regeneration.

To measure BMI1’s effect on heart regeneration, Cohen’s team compared the rate of cardiac healing in normal infant mice against BMI1-knockout infant mice. They found that the mice without the BMI1 gene had a reduced ability to renew cardiac muscle tissue, suggesting that BMI1 “is an important regulator of cardiac regeneration,” Cohen said.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., claiming the lives of more than 600,000 people per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Identifying key regulators of the cardiac regeneration process is an important step toward potential regenerative therapies such as gene therapy or pharmaceuticals” Cohen said.

Working with doctors and students from both veterinary and human medicine really enhanced the team’s collaboration and Cohen’s understanding of the research, she said. “It helped us maintain a holistic view.”

To assess the regenerative capacity of the neonatal mouse heart after ischemic injury, histological analyses were performed after coronary artery ligation. By 21 days after myocardial infarction, there was little evidence of fibrosis when using Masson’s trichrome staining.

This study was a part of the NIH’s Summer Internship Program in Biomedical Research for Veterinary Medical Students.

Efforts continue to eliminate rabies in Ethiopia

Up to five students in The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine’s Summer Research Program are chosen each summer to be supported for international research to work on projects in various parts of the world.

Second-year veterinary student Sarah Waibel is spending her summer in Gondar, Ethiopia, to continue the “Rabies Elimination Outreach Project,” which has been funded by Ohio State’s Outreach and Engagement since 2013. Ethiopia has the world’s second-highest human rabies incident rate, which makes it a One Health global preference location to help address and eliminate the disease.

In the U.S. it is commonplace to have our pets vaccinated for rabies – an effort that has decreased the country’s human rabies cases to about 2 or 3 per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Ethiopia, there are an estimated 1,456 human fatalities per year according to Rabies and Infections of Global Health in the Tropics (RIGHT), a partnership between Ohio State, the CDC, University of Gondor and Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Dogs are the largest transmitters of the disease, accounting for nearly 95 percent of all human rabies cases in the world, according to the World Health Organization.

Although many wild animals can transmit rabies to humans, we tend to interact with dogs more, especially in Ethiopia where dogs are known to roam freely around communities. Therefore it’s believed that vaccinating the dog population will significantly reduce human rabies cases.

Two young locals relax with their dog, which often roams the community, in Gondar, Ethiopia. Photo taken in July 2014 by Dr. Wondwossen Gebreyes, professor of Veterinary Preventive Medicine and Director of Global Health Programs for The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine

Last summer, the dog population in Gondar was estimated by the RIGHT team, which included another Ohio State student in the Summer Research Program Alexandra Medley. The 2014 team recorded the number of dogs observed on a representative sample of the streets by surveying people in 13 urban, semi-urban and rural areas of the city. Now that researchers have this information, Waibel will be working on surveillance and monitoring of rabies cases in Ethiopia to better understand what the effective vaccination rate of dogs is to create widespread immunity, she said.

Waibel will additionally be working with the CDC on surveillance monitoring of reported bites and rabies cases in Ethiopia. She’s also studying Mycobacterium bovis, a bacterium that causes tuberculosis in cattle. Humans can contract the disease by drinking unpasteurized milk, which is a common practice in Ethiopia. Her principal advisors are Dr. Wondwossen Gebreyes, professor of Veterinary Preventive Medicine and Director of Global Health Programs for The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Dr. Jeanette O’Quin, clinical assistant professor in Veterinary Preventive Medicine.

“I’ve always had a fascination in finding out how and why things work,” Waibel said.

She will be discussing what she and her team found at the Third International Congress on Pathogens at the Human-Animal Interface (ICOPHAI) in Thailand this August.

The effort is shared by many partners, including the Ohio State Colleges of Veterinary Medicine, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, and Public Health; the University of Gondar; Ethiopian Public Health Institute; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Federal Ministry of Health and Agriculture, Ethiopia; Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority and the Pan African Union Vaccine Institute.

Acute Lung Injury in influenza patients

Patients with severe cases of influenza sometimes develop Acute Lung Injury (ALI), a highly damaging condition that can be fatal. Treatment options are limited.

MicroRNA (miR) are non-coding RNA molecules that take part in the regulation of gene expression, and they’ve been observed to act abnormally in inflammatory diseases, some forms of cancer and more.

Last summer, third-year veterinary student at The Ohio State University Leon Schermerhorn studied the molecular structure of influenza-induced ALI lung cells and, with his team, was able to conclude that a single miR, miR-155, may play a direct role in the progression of the disease. The team, led by associate professor in Ohio State’s Department of Veterinary Biosciences Dr. Ian Davis, discovered this by determining all miR expression levels in ALI lung cells. The results showed that miR-155 was highly over-expressed by alveolar type II (ATII) cells , which are the primary site of influenza virus replication. As influenza increases in severity, miR-155 expression becomes greater. This is harmful because an upregulation of miR-155 seems to provoke a raise in several types of white blood cells and signaling proteins, causing lung inflammation.

Since miR-155 expression by ATII cells could be responsible for the progression of influenza-triggered ALI, Schermerhorn and Davis hypothesize that miR-155 may be a target for therapeutic intervention. Influenza-induced ALI becomes less severe in mice that ATII cell miR-155 expression has been blockaded, called miR-155-knockout mice.

This summer, Schermerhorn is testing a gene therapy method’s ability to delay onset or reduce severity of influenza-induced ALI in mice. The method involves inserting pieces of specially engineered DNA – in this case lipoplexes carrying antagomiRs – into mice that will target ATII cells and inhibit miR-155 expression. His results will give further data on the role of miR-155 in influenza development in general, as well as the efficacy of inhibiting ATII cell miR-155 expression with antagomiRs.

“Research in public health and infectious diseases has always interested me; I like to solve problems,” Schermerhorn said. “Since influenza is a high-consequence pathogen, this study was a good fit from the start.”

Measuring benefits of environmental enrichments on dairy calves

To prevent the spread of infection and disease, dairy cattle farmers separate calves from each other for approximately six weeks until they are weaned from milk. Though beneficial to health, this practice may hinder calves’ social and cognitive development as well as lead to abnormal habits.

Young calves sometimes display excessive sucking and licking behaviors, often directed toward inappropriate sources such as the enclosure or another calf. As they progress through life, the behaviors can become quite exaggerated and harmful, said Dr. Katy Proudfoot, assistant professor in Veterinary Preventive Medicine and extension specialist in animal welfare and behavior at The Ohio State University. Letting calves feed naturally rather than from a bucket can help reduce this habit, but many producers are hesitant to adopt the practice.

“Veterinarians were the ones who first came up with the practice of separating dairy calves, as a vital health precaution,” Proudfoot said. “But now we’re recognizing that creating a more complex environment could help calves later in life.”

Ohio State veterinary student Emily Cosentino works with dairy calves at Waterman Dairy Center in Columbus, Ohio, as part of the school’s Summer Research Program.

Hannah Manning and Emily Cosentino, second-year veterinary students at The Ohio State University, are working under Proudfoot’s direction and studying the impact of four environmental enrichments on individually housed dairy calves. They hope to see improved social skills and overall welfare in calves who are provided the enrichments, as well as decreased sucking behaviors. They include a slightly larger pen size, a brush to rub up against, an artificial teat and rings to suck on and a tube filled with molasses to stimulate licking behavior.

The team is looking at ten calves in each group – one with environmental enrichments and one without – at Ohio State’s Waterman Dairy Center. They are continually capturing video footage of the calves during their research so they can analyze it from start to end.

“I’ve never had experience with dairy cows,” Manning said. “Working with them this summer has taught me patience and shown me that there’s still a lot more we can figure out.”

Second-year Ohio State veterinary students Hannah Manning (left) and Emily Cosentino (right) at Waterman Dairy Center in Columbus, Ohio, in August 2015.

The study is mostly preliminary, and will produce data about the relationship between calf housing and animal welfare. If the enrichments prove to be beneficial, the team thinks it would be realistic for dairy cow farmers to start providing similar elements to calves.

Health and habitat analysis of endangered Ohio rattlesnakes

Katie Backus, second-year veterinary student at Ohio State (left), acquires a blood sample from a massauga rattlesnake in northeastern Ohio in the summer of 2015.

This summer, second-year student at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine Katie Backus completed a comprehensive health analysis of massasauga rattlesnakes in partnership with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. The data will be studied along with land use and habitat condition.

Eastern massasauga rattlesnakes dwell in northeastern regions of the U.S., including Ohio. The species has been a candidate for the Federal Endangered Species Act since 1999, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The decline of massasauga rattlesnake populations is mostly due to human and agricultural activity as well as habitat loss or destruction. The snakes typically inhabit wetland areas.

The research team tracked and captured massasaugas to acquire blood samples, swab tests for fungal disease and height and weight measurements. They’re also reviewing data on water quality, vegetation density and land use in surrounding areas. Water that flows downstream from farms may contain chemicals associated with agricultural runoff, which has been observed to cause adverse effects in other species.

“Agricultural runoff could be weakening massasaugas’ immune systems,” Backus said, “Possibly predisposing them to fungal diseases and other health issues.”

Backus and her team, led by Greg Lipps, amphibian and reptile conservation coordinator and conservation biologist, were able to capture approximately 55 massasaugas in northeast Ohio. Around 20 were recaptures. The results from fungal disease tests are still processing.

To capture the massasaugas, Backus and her team would walk around in protective gear with snake tongs and bags. Once captured, they would guide the snakes head-first into a plastic tube to prevent biting (as they are venomous), to perform diagnostics. A stress measure – a hormone called leptin – was taken into account during the health assessment.

The results of the study will help the ODNR with conservation efforts, as not much is currently known about the relation between massasauga health and habitat. The ODNR will likely try different techniques on different plots of lands to see what works for the snakes, Backus said.

“I learned so much throughout this process,” she said. “Not only handling snakes, but about government wildlife departments, the history of Ohio’s environment and ecology in general.”

Veterinary medicine plays many roles, and conservation medicine is an important one. This study is an example of how veterinary research can intertwine factors of human, animal and environmental health.