Bats in North America have been dealing with their own infectious disease called white-nose syndrome — and it’s had a much higher death rate than COVID-19 in humans.

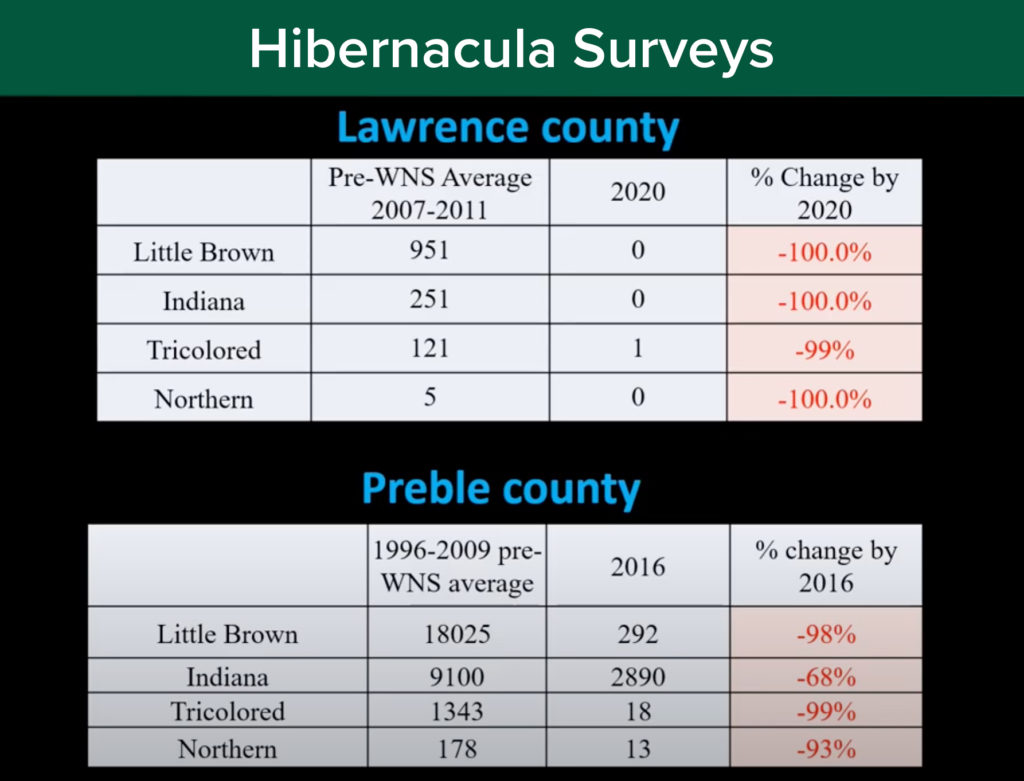

Caused by a non-native fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, white-nose syndrome has devastated Ohio’s bat populations since spreading to the state in 2011, said former Ohio Division of Wildlife Technician Sarah Stankavich.

“The fungus likes the cold, so it actually grows on the bodies of the bats when they’re hibernating,” said Stankavich, who now works for Bat Conservation International. “Infected bats become irritated and continually wake up from hibernation, burning through the fat stores they need to survive the winter when there’s not any insects for them to feed on. They end up dying of starvation.”

Some bat species have been more affected by white-nose syndrome than others, particularly the little brown bat, northern long-eared bat and tri-colored bat, which were all listed as endangered in Ohio in 2020. Of these, the tri-colored bat is probably the least understood, said Mattea Lewis, who’s been tracking tri-colored bats for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources as part of a study funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“There are not a lot of summer records for these bats in Ohio post white-nose syndrome, but we think they roost (nest) in foliage and dead leaves, as well as in bark and tree cavities like other bat species,” Lewis said, adding that tri-colored bats are currently being considered for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act. “We’re trying to learn more about their behavior and habitat preferences so we can recommend unique management strategies.”

To find tri-colored bats — which are so small they’re often mistaken for moths — Lewis has travelled to various bat hotspots in the state to set up mist nets, which are large mesh nets (up to 25-by-60 feet) suspended between two poles to entangle nearby flying bats. Captured bats are assessed for health and tagged with radio transmitters before being released so they can be tracked back to their day roosts.

“I hope this data can lead to some management actions that can help increase the remnant tri-colored population,” Lewis said. “If we know what to protect and what areas they’re using, we can better manage for the species and overall try to get the numbers up.”

Why do bats matter?

Beyond being an evolutionary wonder as the only mammal capable of true flight, bats are hugely beneficial for controlling insects, saving an estimated $3.7 billion per year in reduced crop damage and pesticide use. Tri-colored bats, for instance, can catch insects like mosquitos, flies and beetles as quickly as every two seconds. Outside of Ohio, bats are important pollinators and seed dispersers of fruits like bananas and agave, and scientists have increasingly looked to bats for inspiration in medicine and engineering.

How can Ohioans help bats?

One of the first steps is adhering to land-management recommendations laid out by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and Ohio Bat Working Group, including no tree cutting or trimming from April 1 – Sept. 30, Stankavich said.

“Leave as many potential roost trees as possible — dead or dying trees of any size; trees with loose, peeling bark or cracks and crevices; and trees with clusters of dead leaves,” she said. “Even after the young can fly, bats are going to continue to roost in trees until they leave for their winter migration or they hibernate, which usually starts in October.”

Lewis encouraged installing bat boxes or joining citizen science efforts such as acoustic surveys to record echolocation calls, which help estimate bat presence (citizen science data even helped Lewis identify one of her bat survey locations this summer).

“There are just endless questions that have yet to be answered for bats,” Lewis said. “They’re very elusive, secretive creatures, but they’re so fascinating — they never fail to amaze me.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “there is currently no evidence that the virus that causes COVID-19 is present in any free-living wildlife in the United States, including bats.” Learn more about bats and COVID-19.

Comments are closed